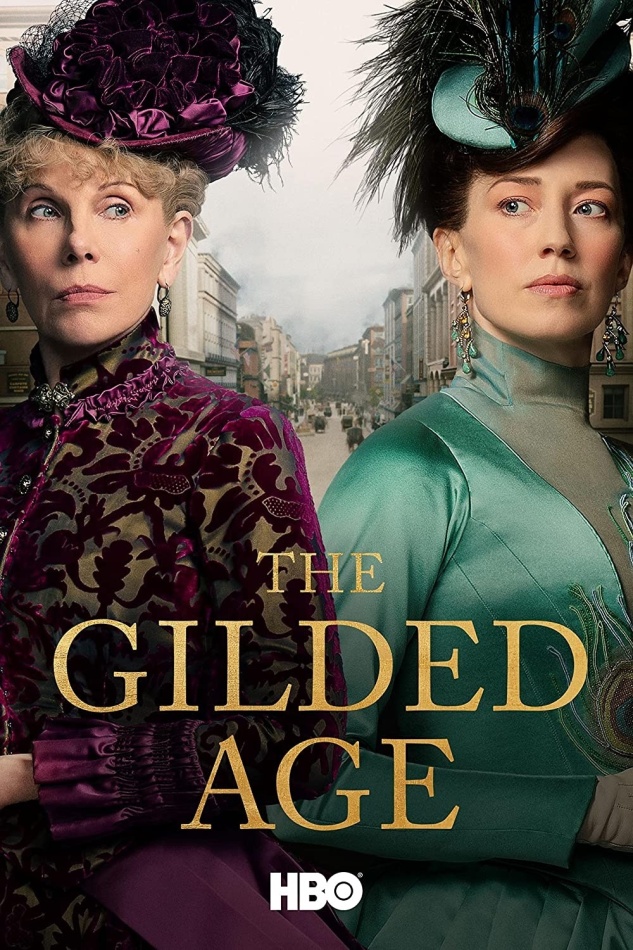

Lately the only thing I’ve been wanting to watch during my downtime is period dramas. Something about the coziness of low-stakes drama fits with the coziness of the holiday season. I burned through Hotel Portofino on PBS Masterpiece; I dipped my toe into Apple TV’s (largely silly and CW-like) adaptation of Edith Wharton’s The Buccaneers. But the one that has really captured my attention is HBO’s The Gilded Age, whose second season is now airing.

Created by the same guy that did Downton Abbey, The Gilded Age follows a similar upstairs-downstairs approach but moves the focus across the pond to 1880s New York. The drama follows Old New York society—big money, bigger dresses—as they are infiltrated by the audacious new money Russell family (based on the real-life Vanderbilts). Mrs. Russell is a scheming queen whose only goal is to secure a spot at the coveted Academy of Music opera house (and to marry her daughter off to the richest, most impressive man she can find). Mr. Russell is a robber baron, a ruthless railroad tycoon who will extort anyone and everyone in order to support his wife’s ambitions. Truly, they are the power couple to end all power couples. The drama, in comparison to other shows, is very low stakes and ridiculous (one of the climaxes concerns a character walking dramatically across the street), which is appropriate for a show whose namesake, coined by satirist Mark Twain, denotes a “period of gross materialism and blatant political corruption.” Edith Wharton’s famous Gilded Age-era novel The Age of Innocence is full of contempt for the Old New York families and their highly rigid, Anglophilic society (“gilded”, of course, refers to the thin sheet of gold that hides less glamorous material). Still, it makes for engrossing television!

The show’s second season delves into more serious subject matter by tackling the plight of railway workers and their long fight towards unionization. After years of being subjected to horrendous (and dangerous) working conditions, the railway men take up the chant “Eight! Eight! Eight!” as they demand an eight-hour workday, eight hours for sleep, and eight hours of recreational time. It’s fascinating to watch the structure of our own modern lives be wrestled into shape by the hands of these working class men—a structure that has somewhat broken down in our technological age (how many of us take work home, or stay in the office past the allotted eight hours?), but one that we have been lucky to benefit from. (Jenny Odell’s insightful How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy discusses the formation of 19th century unions as an early form of protection against soul (and body) crushing capitalism). These workers placed themselves in the literal line of fire to advocate for change.

There is also a more serious exploration of the experience of Black New Yorkers at the time, particularly the Black upper-middle class in Brooklyn. Secretary and aspiring journalist Peggy Scott is a significant side character from a prominent Black family, whose father owns a successful pharmacy and believes her journalistic aspirations are beneath their family’s status. It’s a depiction of Black society in American history that is seldom seen, and season two digs further into this history by having Peggy visit the post-Civil War South (spoiler: it’s bad) and fight against racist policies for the continued education of Black students in New York (for an in-depth look into the history of Black communities in Brooklyn, take a look at Brownstoner’s six-part blog series).

The time period also includes vast, lifechanging technological advancements. Something I’ve been thinking about lately, particularly when observing the younger people in my life, is our depressing lack of wonder. At some point, wildly impressive feats of technology became common place, and each new advancement is either met with only mild interest (“Oh, that’s cool”) or dread (“What happens when corporations/bad actors get their hands on this?”). We already have methods of instant communication that break the barriers of time and space. We can watch, read, or listen to anything we want, at any time. Questions that used to be asked at libraries (“Why do 18th century English paintings have so many squirrels in them?” “What is the natural enemy of a duck?”) can be answered with a quick internet search. I’m old enough to remember the excitement of sending my first text message (something like “We’re in line for the Minebuster” at Canada’s Wonderland); I thought “wow, this is a game changer.”

The characters of The Gilded Age live in that perpetual state of wonder at the rapid technological advancements of the era. One of the most moving moments of the first season concerns Thomas Edison lighting up the New York Times building with electric light, the spectators reacting with shock and awe. Similarly, season two includes the unveiling of the Brooklyn Bridge, a marvel of engineering celebrated with an ostentatious display of fireworks that brings out the entire city. It feels like something we’ve lost in recent years, this ability to be wowed. How do you impress people who have it all? (If this is something you also feel, author Katherine May explores this subject in her latest book Enchantment: Awakening Wonder in an Anxious Age, hoping to help us rekindle that sense of wonder and connection to the world).

Interested in learning more about this unique era? You’ll want to check out Wharton’s work, as well as the following books:

- Astor: The Rise and Fall of an American Fortune (the Astors themselves make appearances in The Gilded Age, as Mrs. Astor presides over New York society)

- The Republic for Which It Stands: the United States During Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, 1865-1896

- Consuelo & Ava Vanderbilt: The Story of a Mother and Daughter in the Gilded Age (you’ll find a lot of similarities between young Gladys Russell and her domineering mother here)

- Diamonds and Deadlines: a Tale of Greed, Deceit, and a Female Tycoon in the Gilded Age (a look at the rare female business tycoon and the burgeoning women’s suffrage movement)