OK, now we’re starting to get into more specific ocean inhabitants. We’ll be focusing on cetaceans (whales, dolphins, and porpoises) this week before moving on to molluscs in the next installation. And while we’re on this topic, something exciting’s going to be coming to FYL on Mondays for the next few weeks throughout the summer, so this series is going to be coming in slightly more sporadic spurts as a result. Now, onto cetaceans! I’m going to be highlighting a few different types of books so that hopefully everyone will be able to find something that suits their reading needs, from those who absolutely adore reading scholarly articles to those who are interested in something with a bit more narrative, whether it be fiction or memoir.

OK, now we’re starting to get into more specific ocean inhabitants. We’ll be focusing on cetaceans (whales, dolphins, and porpoises) this week before moving on to molluscs in the next installation. And while we’re on this topic, something exciting’s going to be coming to FYL on Mondays for the next few weeks throughout the summer, so this series is going to be coming in slightly more sporadic spurts as a result. Now, onto cetaceans! I’m going to be highlighting a few different types of books so that hopefully everyone will be able to find something that suits their reading needs, from those who absolutely adore reading scholarly articles to those who are interested in something with a bit more narrative, whether it be fiction or memoir.

Starting off with something that probably has the greatest appeal in terms of how broad its audience might be, The Stranded Whale by Jane Yolen is a great book with which to complement the ROM’s whale exhibit! Yolen & Cataldo have done a wonderful job in depicting the little girl and her experience with a beached whale, continuing to explore how this event has affected the girl and her community. The Stranded Whale tugs at your heartstrings while providing some facts about stranding at the end after the story, which I think is a great way to start discussion about strandings as well as about whales in general. Going to the ROM would be great either before or after this book, as you’ll learn all about one of the possible futures for the whale that got stranded in this book: having its bones live at a museum.

A great follow-up for an older audience would be The Cultural Lives of Whales and Dolphins, which I’ll discuss in more detail below, where you will learn that some whales actually beach on purpose. (No, they’re not trying to commit suicide… or are they?)

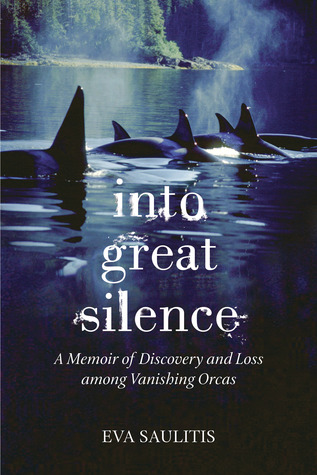

Into Great Silence by Eva Saulitis

Into Great Silence by Eva Saulitis

This is a memoir that focuses on the Chugach transient killer whale pod, otherwise known as the AT1s, located in and around Prince William Sound, and how the Exxon Valdez oil spill affected them as the top predators of the food chain, narrated by Saulitis, who had her first encounter with them right before the spill. Heartbreaking, with little promise of recovery on the part of the Chugach transients, this memoir is a beautiful portrayal of what it was like to come to know these killer whales and to observe their decline. It is all the more poignant for knowing that killer whales are long-lived animals, and the connections Saulitis draws between the inevitable loss of the culture the killer whales share and the loss of the last native Eyak speaker. The intimacy Saulitis feels with these killer whales is palpable throughout, but it is at the very end, when she comes into the closest physical proximity with Eyak than she has ever done before, that it is all brought into heartbreaking relief.

The Whale Who Changed the World by Mark Leiren-Young

How did we even get it into our heads that we should be able to capture animals the size of whales and have them live in captivity? Turns out, it was kind of a fluke. The killer whale that got captured – Moby Doll – was supposed to be killed, then measured while still in the water (so that the size would remain accurate), and then be used to create a life-size model of the creature for display purposes.

Moby Doll became an instant celebrity (surprise surprise), and people lined up just to get a glimpse of him (yes, him, because he was not properly identified as a male until after death), even though he mostly just swam around in circles, listless. He refused to eat for a while, and was moved around a couple of times – you can imagine how difficult it was to procure a proper aquarium for him – before seeming to warm up to his caregivers. All in all, there was quite a bit of drama surrounding Moby Doll, and it’s quite an interesting read seeing how this one killer whale helped change popular perception of these animals so that both the public as well as the scientific communities could view and study them without the same bias as before. Not that they’re gentle giants, all of them, but Moby Doll helped to broaden people’s perspective on killer whales, to consider that they might have nuanced lives and even – culture.

And speaking of culture, there are so many instances of what might constitute culture in cetacean societies as outlined by Hal Whitehead and Luke Rendell in The Cultural Lives of Whales and Dolphins! It’s absolutely fascinating and I can’t recommend this book enough! I found this volume to be a great foundation upon which to read the other books in this post, and it brought up a lot of questions for me when I did read Into Great Silence as well as Are Dolphins Really Smart?, because some of the information seemed at odds with each other across books. I discuss this a bit further down.

It is written in a somewhat denser way (with physically denser type as well), so it may come across as intimidating at first glance. (For post-secondary students, it may look and sound very similar in style to articles you’ve been assigned in class, which may either strike you as an attractive feature or something to regard with absolute disgust – I won’t judge.) Either way, do not let that put you off reading this delightful volume! It is well laid out and organized such that it is very easy to follow along, and the authors take care to explain where they stand as well as opposing viewpoints, which I feel is, unfortunately, rare in the books I pick up. It’s always a delight when authors are upfront about it! And I know I’ve said this before about other books, but I always feel the need to point out how important it is to define terms, especially when what’s under discussion is something as nebulous as “culture”, and Whitehead & Rendell do a pretty in-depth coverage of the various meanings that have been meant by the term before detailing what the definition is that they are going with for the rest of the book. Greggs (below) also does the same for the term “intelligence”, which is another one of those terms mired in ambiguity.

As for the contents of The Cultural Lives of Whales and Dolphins, I don’t want to go too in-depth, because the authors cover a lot of ground, but here’s a quick outline:

- What do we even mean by the term “culture”? (This is a stickier concern than you might think at first.)

- Possible evidence of culture in dolphins and whales, each meriting their own chapter, where social learning is the key argument (e.g. humpback whale songs, sponging foraging behaviour in some dolphins).

- Why Whitehead & Rendell believe these observations merit the term “culture”. They present background information, their own arguments, their opponents’ arguments, followed by their responses to those counterarguments. It’s pretty grand.

- They even state point blank that yes, there is room for doubt and you could explain some of the observations away from being culture. But then they explain why they think it’s culture (it’s a more elegant explanation sometimes, for starters), and the certainty with which they can tack on the label of “culture” to these behaviours.

- Why culture might have evolved and what byproducts tag along, one of which might be… stupidity? (This in relation to stranding and in explanation of group strandings.)

- A treasure trove of endnotes, followed by pages upon pages of bibliographical information. I rarely actually look at the bibliographies even when they’re given, but I had a couple of things I wanted to read more about in-depth because Are Dolphins Really Smart? by Justin Gregg covered some of the same information… except presented in a very different slant. So it was great to be able to check in on both books’ notes sections and find that, yes, they used the exact same sources for the two instances that I wanted to double check, and that yes, there is enough information in the citation for me to search it up on my own and see what the original articles say. As I said, I rarely do this, but it’s great that I actually have the option to do so!

In summary: READ IT.

As a slight aside, If you’ve read Palumbi & Palumbi’s The Extreme Life of the Sea, you might remember there’s a fascinating little note about how both sperm whales and giant squid are less genetically diverse as a species than might be expected, and how a genetic bottleneck might be the explanation behind that. Whitehead & Rendell present their own take on why genetic diversity is low in sperm whales (and other matrilineal cetaceans, including killer whales). Saulitis and Whitehead & Rendell discuss genetic bottlenecks in both their books, and it got a little confusing because it sounded like they were saying completely opposite things. But it will make sense once you understand Saulitis’ comment as being “for a killer whale population this insular, there is a surprising amount of genetic diversity” rather than interpreting the statement as one that talks to animals in general. This might make little sense to you now, but if you decide to read both books, I was pretty flummoxed for a couple of days. You’re welcome.

I’ve been making a couple references to Are Dolphins Really Smart?, so let’s talk a bit about this one now.

Gregg spends the entire book debunking all the popular dolphin myths (e.g. re: language; their abnormally peaceful societies… their friendly, smiling faces), so if you’re looking for information that confirms what you think you know about dolphins, this is not where you want to go. However, if falling prey to confirmation bias strikes you as something you don’t want to be doing, this is a handy little book to make you rethink the way you approach claims about dolphin intelligence. It’s not all about pulling the dolphin down from its pedestal so much as trying to question the pedestal itself and what it actually means at all: are we approaching studying “animal intelligence” all the wrong way?

Gregg starts with defining what he means when he uses the term “intelligence” throughout the entire book, which is actually a lot more important than you might think: in the vernacular, we might think we know what intelligence means, or that of course we know how to quantify it and thus measure it across the board, but “I think you’ll find it a bit more complicated than that” (as Goldacre put it). As a whole, I personally think Gregg might have pushed the message that dolphins aren’t anything that we think they are just a bit too forcefully, but it was definitely quite refreshing right after reading The Cultural Lives of Whales and Dolphins! Besides which, although I would have enjoyed a slightly more magnanimous approach to debunking dolphin myths (this resembles more a single-sided demolition), it’s also undeniable that dolphins enjoy a public perception that places them well beyond gentle reminders that they might not be able to teleport to Mars and dry, scientific papers that don’t reach much of the general public.

There was a chapter on language and what constitutes language, and how only natural language (i.e. human language) has been able to check all the boxes that render it a Language per se, that I found well explained. Gregg even tries to rank dolphin communication in terms of language, and compares delphinid scores to bees, groundhogs, and other animals across the kingdom to demonstrate how unremarkable dolphins score. For all this, I feel as though the entire book actually banks a lot on the general adoration on the part of the masses in order to appeal to readers: if you still love dolphins despite all that Gregg has now laid out, you have to think about why, and how to justify it. The last paragraph is a very clear stepping out of the role of Gregg, someone who wants to drag dolphins down from their pedestal, to Gregg, who thinks we’re thinking about the pedestal all wrong. I would recommend this book wholeheartedly, except to remind readers that you should complement this with another cetacean book or at least to follow up on some of the topics, because of reasons I’ll detail right below.

I personally found it enlightening in that both Gregg and Whitehead & Rendell (above) use some of the same sources – at the very least, two of the same articles, because I went in looking into specific topics in the endnotes in order to find out more about why they were saying what sounded like different things – except the way they portray the information, and which information they choose to present, change the way the reader would interpret what they take away from the text altogether. This is another reason why I love seeing extensive endnotes and bibliography sections! They make me weak at the knees and there’s a good reason for it, which I don’t really have space to get into here, but suffice it to say that when you’re reading two published books by figures of what you might assume are authority in their fields, and they say even just slightly different things even though they were published just 2 years apart, it’s a relief to be able to check in on which sources they used, when those were published, and how on earth the same source got interpreted in different ways (or interpreted the same way but used for different purposes because the goals of each book were vastly different).

If you’ve made it this far into the post, I’m actually really touched. This is just a quick roundup of links for the Dive Into Reading series that have been posted and that are yet to come:

- Dive Into Reading: General Reading

- Spineless

- Cetaceans

- Mollusca

- General Ocean Reading