In the Harry Potter universe, a sense of cold, creeping dread announces the arrival of Dementors, foul creatures of darkness who sweep away happiness and deal in despair. “Get too near a Dementor,” Professor Lupin tells Harry in The Prisoner of Azkaban, “and every good feeling, every happy memory will be sucked out of you.” Dementors might be real, dangerous monsters for our wizard hero, but for author JK Rowling, Dementors are an avatar for depression. While writing the beloved series, Rowling was suffering from a bout of depression herself, which she described as “that absence of being able to envisage that you will ever be cheerful again. The absence of hope. That very deadened feeling, which is so very different from feeling sad.” This, incidentally, is almost exactly how Lupin describes Dementors to Harry.

In the Harry Potter universe, a sense of cold, creeping dread announces the arrival of Dementors, foul creatures of darkness who sweep away happiness and deal in despair. “Get too near a Dementor,” Professor Lupin tells Harry in The Prisoner of Azkaban, “and every good feeling, every happy memory will be sucked out of you.” Dementors might be real, dangerous monsters for our wizard hero, but for author JK Rowling, Dementors are an avatar for depression. While writing the beloved series, Rowling was suffering from a bout of depression herself, which she described as “that absence of being able to envisage that you will ever be cheerful again. The absence of hope. That very deadened feeling, which is so very different from feeling sad.” This, incidentally, is almost exactly how Lupin describes Dementors to Harry.

Unfortunately for us Muggles living in a boring, non-magical world, things like depression don’t exist in a solid form. We can’t shout “expecto patronum!” at mental illness and chase it away with a helpful Patronus. But there are some steps we can take to combat it, such as the simplest, most obvious, but often most difficult starting point: talking about it. When Harry faints upon his first encounter with a Dementor, he is filled with shame. Nobody else is fainting, so why is he? It isn’t until Professor Lupin opens the door to a conversation that Harry learns why he is so affected by the creatures, and how to fight them off. Today is Bell Let’s Talk Day, a day dedicated to breaking the silence on mental illness through conversation on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Snapchat, and text messaging with the hashtag #BellLetsTalk.

The cynical part of me remains a little dubious about a major corporation claiming to support mental health initiatives, particularly in the workplace (what policies do they have in place that address employee mental health?), but I’m going to try to ignore that little voice and focus on the positive. At the end of the day, any positive conversation is good conversation. Because it does affect us all! Even if you don’t suffer from a chronic mental illness—say, clinical depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety—chances are your mental well-being isn’t always 100%. According to the Canadian Mental Health Association, “In any given year, 1 in 5 people in Canada will personally experience a mental health problem or illness.” Keep in mind, this stat only reflects diagnosed illnesses. Plenty more of us are just out and about self-coping, crippled by stigma. We all have work to do in making mental health just as talked about and prioritized as physical health.

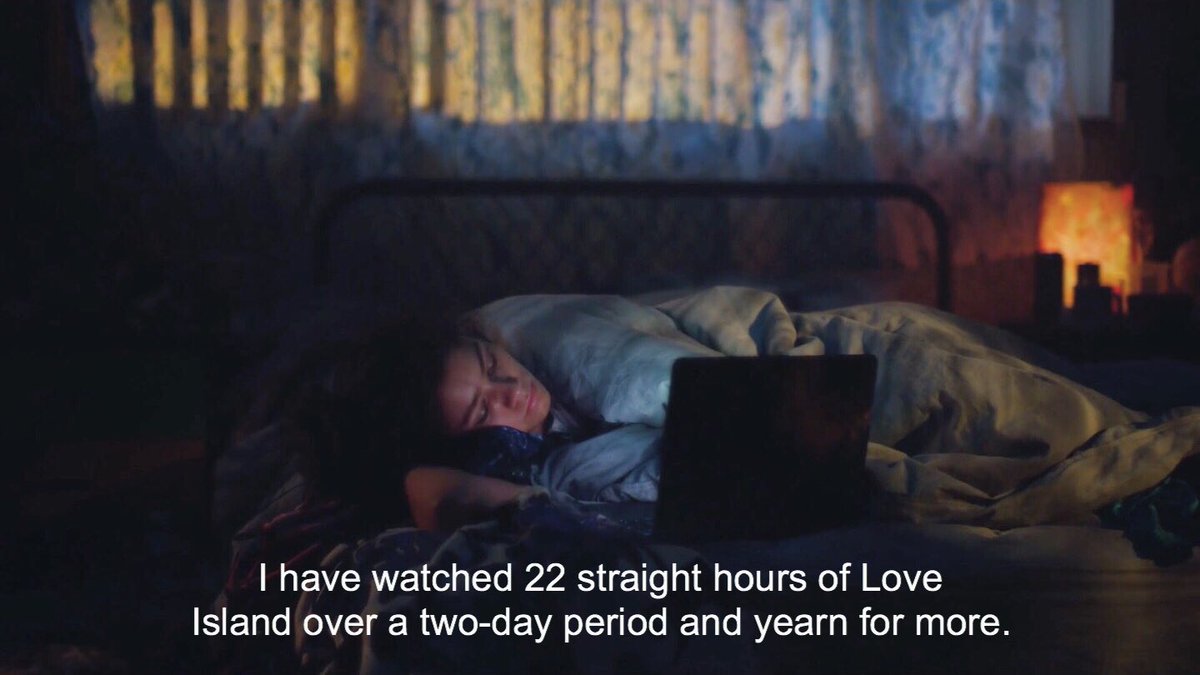

Euphoria ©HBO

If you were to experience an episode of mental illness, would you recognize it? Illness doesn’t always look the way we think it does. Depression doesn’t always manifest as sadness—it’s a shifty devil that can present as anything from poor concentration to appetite loss to binge-watching all of Love Island in a 22 hour span. Anxiety, one of the most common disorders, can simply look like someone too nervous to drive through a certain intersection, or someone stressed out about performing simple tasks. Because these symptoms can be minuscule to outsiders, it’s important for each of us to be in tune with our own changing moods, to recognize when they might be a problem. It’s important to understand when to see a doctor, and when we can mitigate these down-periods on our own or with family and friends.

Thankfully, as awareness is brought more and more into the foreground, mental well-being is on a journey to normalization. With the explosion of social media came an explosion of poor social media habits, leading to a rise in mood disorders; users weren’t aware of the toll continuous online access to peers and strangers would take. Social media was a blazing new frontier in human connection, and most of all, it was fun! But now, a few years later, we have big name celebrities like Selena Gomez, Ed Sheeran, and Lizzo taking deliberate, thoughtful social media hiatuses. As Lizzo put it in one of her Instagram stories, “I be waking up feeling bad as hell, I be waking up in my feelings, and I know that my mental [health], my emotional health, and my social health already affects me in positive and negative ways. But you add the internet to that shit, boy; the internet will have you depressed as fuck.” Adding to that, in a UK survey from 2018, 41% of Gen Z participants admitted that social media use made them feel “anxious, sad or depressed.”

It’s no secret that in the treacherous hellscape that is social media, Instagram is the greatest offender. It’s not hard to see why: a quick scroll through the app and you’ll see everyone’s fakest, most perfect selves. Beautiful apartments, expensive vacations, Photoshopped bodies, one after another after another, naturally leading to anxieties about inferiority and the dreaded FOMO (fear of missing out). I admit that even as someone who knows it’s all fake, I’m still susceptible to feelings of inadequacy. Why isn’t my life as adventurous? Why isn’t my hair perfect? Why am I not having as much fun?! Obviously, the easy conclusion to draw here is stop using social media—but how realistic is that for many of us? Not very. But putting mindful practices into place can help us navigate the bad habit we apparently can’t kick.

A strange—but maybe not unexpected—phenomenon of social media is the ways in which Gen Z and millennials are now expressing their anxieties on the very platforms causing them. There’s been some writing lately on “finstas”: fake Instagram accounts that Gen Z uses as an antidote to their “real” accounts. In a concept that seems a bit turned-around to me, the “real” Instagram account is where the pretty pictures go; the life people want to be seen as having. “Finstas” are for the ugly, unphotogenic parts of life meant only for close friends. Seeing the younger generation seeking out a means of real connection online might signal the decline of Instagram as we know it—almost like perfection fatigue. The decline in “influencer culture” can’t happen fast enough. Aside from Instagram, people are taking to Twitter, Snapchat, and Tumblr (those who are still on it, anyway) to not only openly discuss their struggles with mental health, but to poke fun at them. Last year, Buzzfeed compiled a list of “Therapist Meme” tweets which make fun of unhealthy coping habits. Then there’s the meme about baby boomers being hush-hush about therapy as the younger generations bond over it. And while humour as a coping mechanism isn’t exactly a cure, it goes a long way to slowly dismantling the stigma. When you see just how many people are seeing therapists or otherwise struggling, a sort of online support community forms.

A strange—but maybe not unexpected—phenomenon of social media is the ways in which Gen Z and millennials are now expressing their anxieties on the very platforms causing them. There’s been some writing lately on “finstas”: fake Instagram accounts that Gen Z uses as an antidote to their “real” accounts. In a concept that seems a bit turned-around to me, the “real” Instagram account is where the pretty pictures go; the life people want to be seen as having. “Finstas” are for the ugly, unphotogenic parts of life meant only for close friends. Seeing the younger generation seeking out a means of real connection online might signal the decline of Instagram as we know it—almost like perfection fatigue. The decline in “influencer culture” can’t happen fast enough. Aside from Instagram, people are taking to Twitter, Snapchat, and Tumblr (those who are still on it, anyway) to not only openly discuss their struggles with mental health, but to poke fun at them. Last year, Buzzfeed compiled a list of “Therapist Meme” tweets which make fun of unhealthy coping habits. Then there’s the meme about baby boomers being hush-hush about therapy as the younger generations bond over it. And while humour as a coping mechanism isn’t exactly a cure, it goes a long way to slowly dismantling the stigma. When you see just how many people are seeing therapists or otherwise struggling, a sort of online support community forms.

But even with this support, limiting the amount of social media consumption day-to-day is an important step to mental well-being. Easier said than done though, right? Luckily there are tons of resources on this exact issue, such as How to Break Up With Your Phone or, if a break up is too devastating, Modern Mindfulness. But it would be too simplistic to blame all our struggles on social media. Limiting screen time is essential, yes, but there are other small, simple changes we can make in our daily lives that are like little serotonin boosters. I know we’ve heard it a million times before, but seriously: do your best to eat balanced meals! Go for a walk in the sunshine! Clean your bedroom! Stick to a proper sleep schedule! (This last one is particularly hard for me) If you’re in a place where these things are too hard, scale it back even more: drink a glass of water. Brush your hair. Light a candle. The goal is to find enjoyment in whatever small victories your day brings, and those victories look different depending on your health. I often turn to Meik Wiking’s research on happiness, and Anna Borges’s The More or Less Definitive Guide to Self-Care (Borges recently wrote an excellent piece on her own passive suicidal ideation, adding her voice to the fight against stigma with her opening lines: “passive suicidal ideation is like living in the ocean. Let’s start talking about how to tread water.”). And of course, if you no longer feel in control, talk to someone! Whether or not you require medication, an open dialogue is essential. Let’s talk about it!

- Find out more about Bell Let’s Talk

- Learn more about programs and services at the Canadian Mental Health Association

- Read more with this inclusive list from the Portland Public Library

- Explore a variety of mental illness topics with these powerful personal essays

Thank you for sharing the piece on passive suicide ideation! The subtitle of the article is very telling: “Chronic, passive suicidal ideation is like living in the ocean. Let’s start talking about how to tread water”. Not “how to get to shore”. At one point, the author asks whether the risk of negative social consequences is worth being able to talk about her chronic passive suicide ideation: will those who know become hypervigilant; will their relationship, their interactions, be reduced to this one aspect of her life? And that’s certainly something to consider, because as Anna Mehler Paperny discusses in Hello, I Want to Die, Please Fix Me (https://vaughanpl.bibliocommons.com/item/show/470450130), disclosing mental illness could very well impact things like your insurance. Health benefits. And if you have children, that could have a great impact on their well being and be a very real reason why you can’t talk about your mental health. It’s also very interesting how Borges adopts this perspective of talking about suicide ideation in the wide range of its spectrum as something that should be treated, cured, in reference to the scientific community: “Outside of anecdotal evidence, scientists just don’t know a ton about passive suicidal ideation — which means they also don’t know much about how to treat it”. Does it need to be treated at every stage, or is it really just when it passes a threshold? And what is that threshold? Is it the same three D’s in psychology: Deviance (from the norm), Dysfunction, Distress? (And Danger. I was taught the three D’s, but apparently there is also the four D’s model.) What would life even look like if suicide ideation could be “cured” and no one ever fancied being dead?

Wonderful post as always!

Also this came up in my newsletter subscriptions the other day: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JnHH_EDRlZg (a Mental Health Initiative video series by California Library Services). (I have yet to watch it, but it was recommended by Jessamyn West from Today in Librarian Tabs, so I trust it.)