With Priscilla now out in theatres, I felt the urge to revisit director Sofia Coppola’s work. Coppola has been criticized copiously throughout her 25-year career, first as a nepo baby descending from directorial royalty (her father is Francis Ford Coppola), and second as prioritizing style over substance. My take? Being a nepo baby is fine if you acknowledge your privilege and (crucially) you are talented, and sometimes style is the substance. Or, more accurately, style reflects the substance. It takes skill to have your own visual style, and Coppola, as head Sad Girl of the cinematic world, has that in spades. She is also always reliable for a killer soundtrack, the songs not only exhibiting enduring cool-girl taste but selected for their ability to enhance a specific mood or theme. Priscilla is a continuation of Coppola’s dependable style and music choices, only missing Lana Del Rey, who styles herself after Priscilla Presley (reportedly Del Rey was approached for the soundtrack but turned it down. Too busy working shifts at Waffle House, I guess). Below is a look back at Coppola’s most iconic work.

Coppola cemented her brand early with her 1999 directorial debut, an adaptation of the Jeffrey Eugenides novel The Virgin Suicides. It’s about as on-the-nose Sad Girl as Coppola gets, which makes sense owing to her youthful age at the time (28—which translates to about 12 in director years). The story follows a group of boys who reminisce about the enigmatic Lisbon sisters, who all die by suicide in the year 1975. The girls are young (teenagers), lithe, blonde, pretty, and incurably sad—Coppola trademarks. Her other trademarks are also fully-formed in this debut: a dreamy, hazy atmosphere combined with a controlled and even sparse sensibility, along with an impeccably curated soundtrack whose every song is deliberately used to evoke either Coppola’s dreamy style (such as the score by French dream pop/space pop band Air) or the film’s location in place and time (such as songs by Heart and Styx).

Next comes her most acclaimed film, 2003’s Lost in Translation, which won her an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay and a nomination for Best Director (making her the third woman in history to be nominated this prestigious—and biased—award). Truth be told, I don’t love Lost in Translation, which used to be sacrilege but seems to be more acceptable now that we’re looking back on it from 20 years on. The treatment of Japanese characters leaves a lot to be desired, and there’s just something skeevy about Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson’s (then 18-19 years old) borderline-romantic relationship. It’s not a film that ages particularly well, but it certainly had its place in 2003, and I will admit the last scene (where Murray whispers something to Johnasson that we do not hear) is iconic. Coppola’s depiction of Johansson’s loneliness is also very effective—it’s what she does best, after all.

I had the opposite experience with 2006’s Marie Antoinette: while it seemed to polarize audiences, I absolutely ate it up. Here was another story of a lonely girl, only this time she was saddled with the duties of being queen in a foreign country. Marie Antoinette really sent the style-vs-substance critics into a tizzy: why is the film not more overtly critical of the French aristocracy? Why are there so many purposeful anachronisms (such as the highly controversial Converse sneakers)? Why is the soundtrack mostly 80s music? Are we glorifying or condemning? All boring questions, in my opinion. We already know Marie Antoinette’s end (hint: guillotine); this film is not interested in chronologizing the French Revolution. As always, Coppola is interested in the psychology and emotional reality of the woman at the centre of the story (the film is informed by the Antonia Fraser biography Marie Antoinette: The Journey). And the anachronistic elements serve as a bridge for modern audiences to place themselves in her world. I believe Marie Antoinette to be a bit prophetic, actually. TV shows Dickinson and The Great owe plenty to Coppola’s earlier film, namely the use of 21st century dialogue and a whole-chested disregard for historical accuracy in order to capture modern audiences. Similarly, Netflix’s Bridgerton adaptation is able to use string versions of pop songs with relatively little ire.

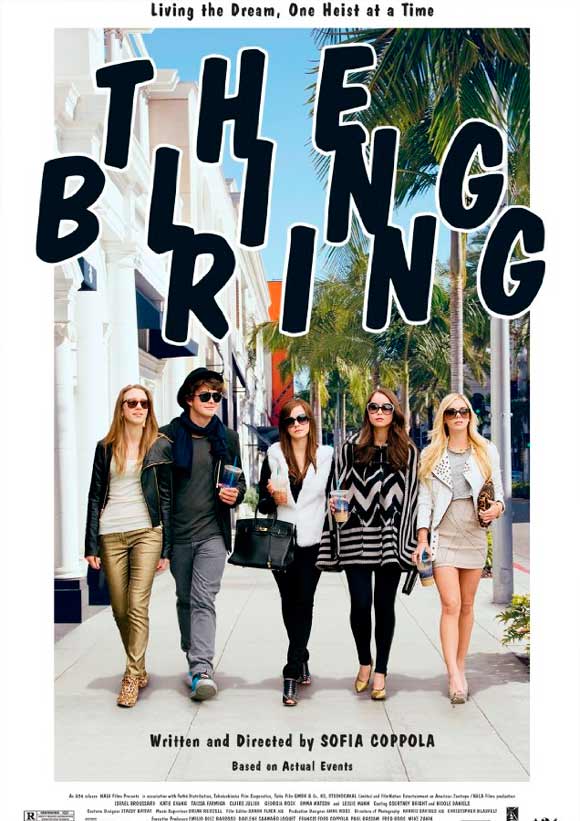

Coppola’s interest in the hollow lavishness of the elite returns in 2013’s The Bling Ring, which is based on the true story of Alexis Neiers and her Calabasas cronies, who famously robbed celebrities in order to fake their way into a life of luxury (the film is inspired by the Vanity Fair article “The Suspects Wore Louboutins” by Nancy Jo Sales). Coppola’s interest here is on the effects of late 2000s/early 2010s reality TV culture on young girls. As usual, she doesn’t outwardly condemn the thieving girls for their criminal behaviour, but explores the environment that created them. The Bling Ring is one of Coppola’s weirder movies, but I think it works, with Coppola’s sparse directing style juxtaposing the girls’ bland, suburban California lives with those of the uber-wealthy they are trying to mimic. There’s an intriguing absurdity to the story that feels extremely 21st century, often found in Neiers’s real-life quotes (i.e. Sales said Neiers wore six-inch Louboutins to court, when actually she wore little brown kitten heels!) and reflected in Emma Watson’s hilarious line deliveries of “I wanna rob” and “I wanna lead a country one day, for all I know.” It also has my favourite Coppola needle drop, “Crown on the Ground” by Sleigh Bells hitting like a punch to the head with the title card.

Lastly, I recently rewatched 2017’s The Beguiled as part of my spooky season lineup, an eerie little film starring heavyweights like Nicole Kidman, Colin Farrell, and (frequent collaborator) Kirsten Dunst. The Beguiled brings back Coppola’s young, pretty, and blonde aesthetics, but this time the inherent sadness and isolation is reflected outwardly in the setting, a once beautiful, now almost decrepit Southern plantation mansion falling to rot. A group of genteel Southern women and girls are holed up in this mansion, trying to maintain a routine during the Civil War when an injured Union soldier pierces their bubble of womanhood. Coppola’s sparseness works well here: crisp white dresses, simple wooden furniture, and a sense of luxury lost. Pervasive darkness enhances the sense of isolation, as often the only source of illumination in a scene is a candle or lantern (this is particularly effective in a scene towards the end, when Farrell, the soldier, joins the women at the dinner table, their faces eerily lit from below). The Beguiled courted some controversy as it eliminates an enslaved character found in the source novel (the film notes that enslaved people have run away). Coppola says she didn’t want such a heavy topic to be treated lightly in her version, and so she chose to eliminate it rather than brush over it. Still, this may have been a way for Coppola to venture outside her white girl comfort zone. The film as it is hews very closely to her established brand.

Are you a fan of Sofia Coppola? Do you have plans to see Priscilla? Let us know your thoughts!