I’m out of the country! So, after last year’s posts on Alaska, I’ve decided that this year’s trip should influence a post, too. Where am I this time? If you skipped reading the title when this post goes live, I’m probably getting fat on dim sum, seafood, and roast goose in Guangzhou, China, after visiting Chongqing and Chengdu earlier in the trip. Hot pot, dan dan noodles, mapo tofu, kung pao chicken; I’m returning at least a kilogram heavier from this trip with an even higher heat tolerance than I currently have. My wife and I make some of these dishes at home, but that’s never quite the same as getting them right from the source. And since Chinese cuisine covers so much ground, it’s nice to eat the things we don’t make at home too. Not having to cook them ourselves is a big plus, too.

If you’ve read this far and haven’t immediately jumped to a translator, 好吃, if translated literally, is good (好 hǎo) eat(ing) (吃 chī), but can be generally understood to mean delicious. It’s something I said a lot on my first trip to China and something I expect Future Adam will be saying a lot on this trip as well. Can you tell I like 中国菜 (zhōngguó cài) Chinese cuisine? Present Adam, the one writing this post, wishes it was already time to head off on vacation, but I know I can at least fill some food cravings here at home1.

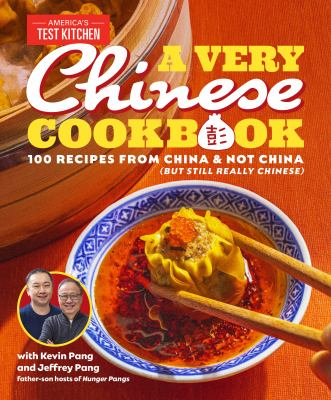

As footnote 1 issues out, it’s very easy to find recipes on the web. But you know what those recipes lack in a lot of cases? Editing. And if you’re making something with only a few reviews, good luck, because who knows what abomination you might turn out from an untested recipe. That’s why cookbooks are still one of the most popular items in our adult fiction section, and today’s book provides thoroughly tested recipes similar to stuff my wife makes. Admittedly, much of what she does comes from watching video recipes, reading comments from people who have made it, and getting ideas to improve it from those comments. Like me, she let her parents handle most of the cooking when we were growing up, so now we both need to develop our skill sets further. I’m not always a proponent of dead-tree books, but at least with a physical book you can flip to a recipe and get right into it without scrolling through ten screens3 of time-wasting preamble, and there’s no jumping back and forth in a video to keep track of.

Speaking of preamble, it’s book time! I’m only highlighting one cookbook in this post: A Very Chinese Cookbook: 100 Recipes from China & Not China (But Still Really Chinese), which comes to us from Kevin and Jeffrey Pang of America’s Test Kitchen’s Hunger Pangs YouTube channel. The tone in the book is irreverent and fun, but the rigorously tested recipes and tips are nothing to laugh at. The first 40 or so pages of this book will help prepare you to cook the recipes within, explaining things like ingredients, tools, and techniques that may not be well-known by those inexperienced with the cuisine. I’m already using a trick learned from the book to make cutting 腊肉 (Làròu, or Chinese bacon, a dried, salty, delicious affair) easier, and in flipping through it, one of the first recipes I came across is appropriate for this post: 担担面 (dàndànmiàn4) or carrying pole noodles. So named because vendors would often sell them from two pots carried over their shoulders, the noodles in one, the sauce in the other. These spicy, numbing, savoury and sour noodles are a staple of Chengdu street food and something I’m absolutely going to try when I’m there.

The following few books are a little different; rather than suggest cookbooks, I’ve gone off course and found some books that look at the history and culture of the cuisine, and for a couple of them, how leaving China changed it.

First up: Invitation to a Banquet by Fuschia Dunlop. Getting the elephant in the room out of the way early: yes, she’s not Chinese. However, she did study at the Sichuan Higher Institute of Cuisine in Chengdu. Kevin Pang mentions her books as an influence on his cooking in the introduction to the Dandan noodle recipe. Suffice it to say, she knows her stuff. Invitation is an in-depth look at 30 recipes, tracing their history and development and describing them in ways that will make your mouth water.

Next up: not a book, just something you can watch on YouTube, and the inspiration for going off on the food-history track. I’ve been saying Chinese cuisine like it’s some kind of monolith, and it really, really isn’t. My wife and I enjoy this channel, Chinese Cooking Demystified, and while we’ve never made a recipe from their videos, we always appreciate how they break down the dish and often try to give some background about where it came from. This video doesn’t offer recipes; instead, think of it as a (very broad) culinary breakdown of the country, showing that ‘Chinese cuisine’ is far from being one thing. Fair warning: you will be hungry by the end of it, with so much delicious Chinese cuisine being talked about/shown, its impossible for there to be nothing that piques your interest.

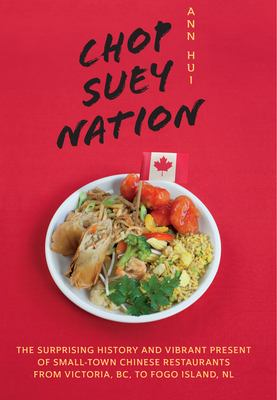

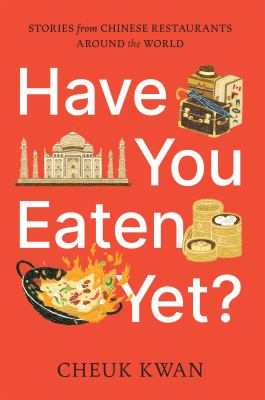

Now, two more books with similar themes: Chop Suey Nation by Ann Hui and Have You Eaten Yet? by Cheuk Kwan. Both focus on the Chinese diaspora opened restaurants where local tastes and available ingredients influence the cuisine. Chop Suey Nation is a road trip across Canada by Globe and Mail Journalist Ann Hui as she speaks to owners of small-town Chinese restaurants, interspersed with her parent’s tale of having owned a restaurant themselves when they first immigrated to Canada. Have You Eaten Yet? is Cheuk Kwan’s memoir of filming his Chinese Restaurants documentary, traveling around the world to visit the same kinds of places Hui visits on her trip. If you’re looking for insight into why Chinese restaurants are so ubiquitous and how their, to steal a phrase from the Pangs, ‘not from China (but still really Chinese)’ menus came about, these books are a solid place to start.

And that’s it for me this month. My day will be ending as this goes up; I wonder what I’ll eat for dinner that day? We’ll probably do dim sum the next morning. I’m getting hungry just thinking about it.

1 My wife and 妈妈 (māmā) 2 have both told me I make restaurant-quality congee. The secret is following the instructions on a website. In my defence, it’s a website run by the son of a Cantonese chef, and it’s the chef doing the cooking. And they’ve won a James Beard award for their work.

2 You get no further help with this one as its exactly what it sounds like.

3 Let’s be honest, I’m being generous, saying it’s only ten screens.

4 By this point, you may be wondering why there are accents over the anglicized pronunciations of the characters. It’s what’s known as pinyin, and the accents indicate which tone to use. Speaking with the right tone has been the most challenging part of learning Chinese as an English speaker, where tones indicate emotion or intent rather than being tied to the direct meaning of a word. It’s surprisingly easy to accidentally call someone’s mother a horse.