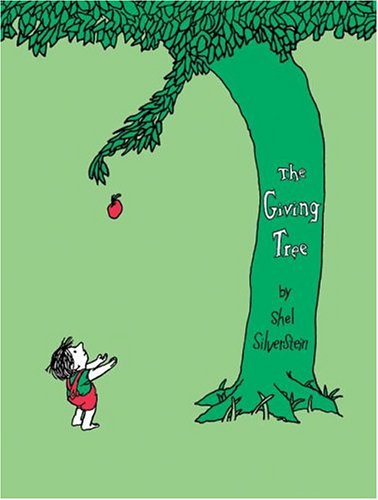

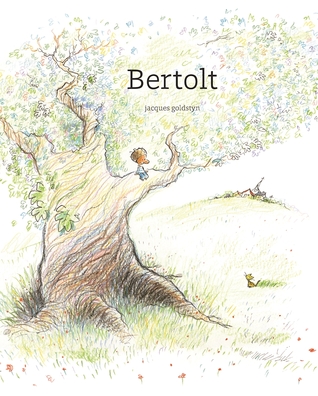

When Bertolt popped up in my periphery, I knew I had to read it, especially in the wake of The Giving Tree. (In case you missed it, you can see my thoughts about Silverstein’s book here.) Like The Giving Tree, Bertolt also features a relationship between a (nameless) boy and the titular tree – I hesitate to say his tree, even though he has named it, because although I think he feels an affinity with it and identifies it as his own, it’s less a matter of belonging or ownership so much as the fact that it is with this particular tree and not another that he has a special connection – but veers into a completely different direction altogether, and it’s both heartwarming and sad because no sooner do we feel the complete love of this boy for the tree do we learn that the tree can no longer give him what his memories hold: Bertolt is dead.

When Bertolt popped up in my periphery, I knew I had to read it, especially in the wake of The Giving Tree. (In case you missed it, you can see my thoughts about Silverstein’s book here.) Like The Giving Tree, Bertolt also features a relationship between a (nameless) boy and the titular tree – I hesitate to say his tree, even though he has named it, because although I think he feels an affinity with it and identifies it as his own, it’s less a matter of belonging or ownership so much as the fact that it is with this particular tree and not another that he has a special connection – but veers into a completely different direction altogether, and it’s both heartwarming and sad because no sooner do we feel the complete love of this boy for the tree do we learn that the tree can no longer give him what his memories hold: Bertolt is dead.

In light of this, the boy meditates upon the death of his friend, Bertolt, the big oak tree, and is thrown into a sort of controlled turmoil: were Bertolt to have been struck by lightning or cut down, at the very least, the boy says, he would know for sure. His excitement during the winter served to sadden him even further once spring came around, and the fact that he never realized when exactly it was that Bertolt’s life quietly ended only compounds the realization that this year, this spring, will be different from all the springs past. The little boy thinks about what he can do to remember Bertolt and all the fun times they had together – getting to know the inhabitants of the big tree, climbing up to people-watch the inhabitants of the city – and comes up with a beautiful idea to give the tree its foliage once more.