February is Black History Month! To celebrate, VPL has put together programming for all ages, including Black History: The Music and the Message for kids, and an adult book club where we’ll discuss The Skin We’re In by Desmond Cole. For more programming options, check out our What’s On Magazine.

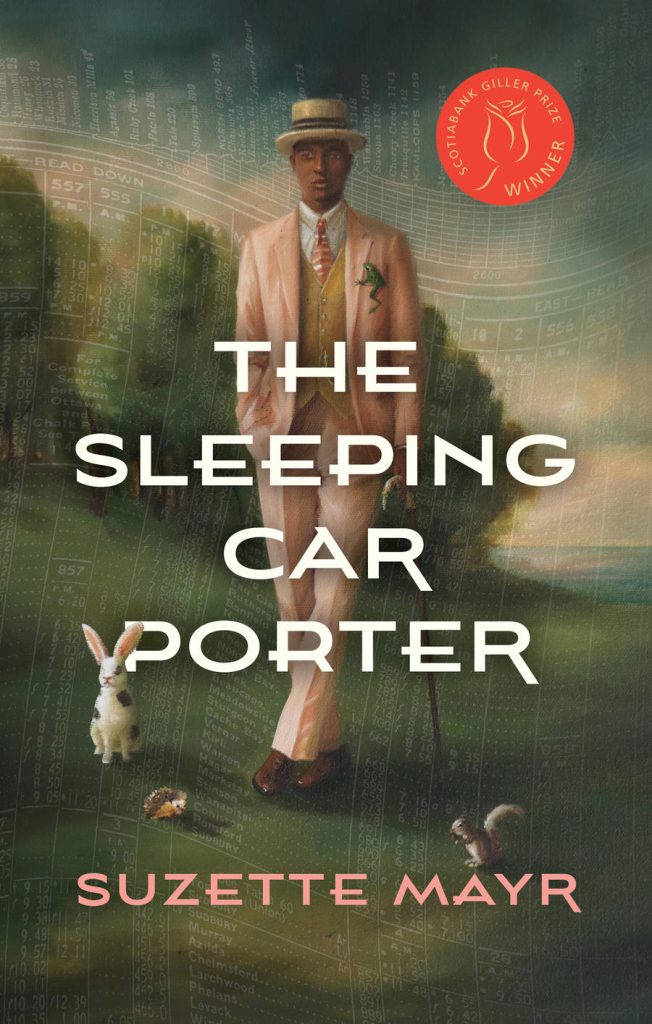

Suzette Mayr’s The Sleeping Car Porter uncovers a portion of Canadian history lost to time—more specifically, Black Canadian history, lost to time due to institutional neglect. The 2022 Giller Prize winning novel follows a young Black man in the 1920s named Baxter, who has come over from the Caribbean for a job as a train porter in order to save up money for dental school. The novel’s timeline is a single cross-country train journey, from Montreal all the way to Banff, during which Baxter’s lack of sleep results in a blurry delirium made worse by the constant demands of his customers.

I’ll admit I knew nothing about sleeping car porter history prior to reading this novel, but there were enough intentionally placed, specific references to suspect that there was likely a well of history behind Baxter’s story. Why, for example, did (white) customers keep calling him George? What was this Brotherhood they keep mentioning? Turning the last page over to Mayr’s extensive bibliography was the final clue that this novel is very, very heavily based on real Canadian history. So like any good nerd, I went on a bit of a deep dive and checked out They Call Me George: The Untold Story of Black Train Porters and the Birth of Modern Canada by Cecil Foster and My Name’s Not George: The Story of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in Canada by Stanley G. Grizzle, two titles from Mayr’s research that are available at VPL. They Call Me George is a particularly useful companion read to The Sleeping Car Porter, as it often answers the questions brought up in the novel. What I learned took me by surprise: Black porters were not only part of the Canadian cultural consciousness of the early to mid-20th century, they were also instrumental in instigating a Black middle class, and even helped cement—not by accident, but by will—our identity as a multicultural nation, on which we now pride ourselves.

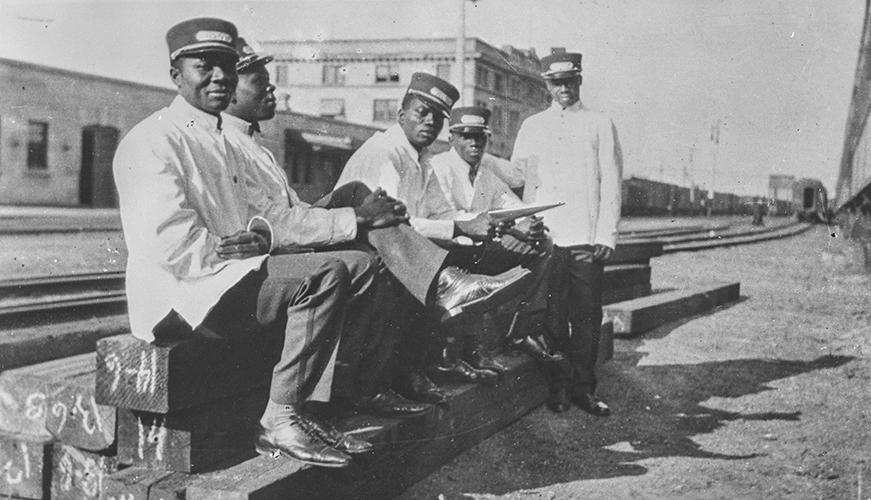

A sleeping car porter’s job was essentially to play servant to the moneyed class traveling long distance on sleeper trains, and the Canadian version of this type of service (which operated on the Canadian Pacific, the Intercolonial, and the Grand Trunk railways) was based on the American Pullman service. Pullman service was founded by George Pullman and was modeled on the service found in Antebellum great houses—the time period in which slavery flourished. With slavery eventually abolished, Black men were in search of employment, and as Foster argues in They Call Me George, Pullman felt the role of servant was a natural fit for these men, as his white passengers would be used to Black servers. These men were condescendingly referred to as “George’s boys”, and eventually just “George.”

When this service was adopted in Canada, the image of the Black porter was already established. And so Canadian railways recruited their porters from the American South and the Caribbean. And while there were no official Jim Crow style laws in Canada, the spirit of segregation and racism was undeniable. The job of sleeping car porter was one of the better ones open to Black men at the time, with relatively decent pay and respectability, but there was no option for these men to advance to any position higher than porter (so no waiter, no chef, no conductor positions). The hours were long and grueling, and porters often got no more than three hours of sleep a night (“One of the biggest challenges for porters was to stay awake,” writes Foster), which Mayr vividly illustrates with an increasingly hallucinating Baxter. Meals were not covered, and there was a seemingly arbitrary system of demerits in place which often led to unfair dismissal. Baxter agonizes over the level of familiarity with which to treat his white, especially female, customers; being either too friendly or too reserved could earn him demerits.

The “Brotherhood” mentioned in the novel refers to the Brotherhood of the Sleeping Car Porters, which was established in Chicago and adopted in Canada as a unionized front against these conditions. My Name’s Not George by Stanley G. Grizzle is a detailed account of the fight for fair labour by the porters. Grizzle himself was a former porter and a civil rights activist based in Toronto who helped open the door for Black workers to advance within the railway system, as well as working with the Joint Labour Committee to Combat Racial Intolerance. With the help of these unions and committees, Black Canadians were able to develop middle class communities, especially in Toronto and Montreal. And with these newly established civil rights for non-white folk came the pivot in Canadian identity, one that embraced multiculturalism. Remember, Canada was not founded with inclusive intentions; it was intended to be an offshoot of Europe, and non-white immigrants from other British colonies were often denied entrance. Foster calls official multiculturalism “a fluke of history.” One we should be grateful for, but not one we should take for granted.

So where is this struggle in our common cultural knowledge? One of the reasons Mayr wrote The Sleeping Car Porter was to shine a light on this quiet part of our history—and some real digging was necessary. Black immigrants in the early 20th century had not been considered “Canadian” in the same way as some other citizens, and so not much about them had been preserved. “It was working-class history, so it wasn’t considered important,” Mayr said in an interview with the University of Calgary. This sort of archival silence (that is, voices missing from archives) came up twice over, as Mayr, a queer woman, wanted her main character to also be queer. Finding recorded information about closeted men in the 1920s is not an easy task, as their safety relied upon being unrecorded. Still, in an essay for LitHub, Mayr traces her research steps, which included piecing together fragmented bits of marginalized Canadian history to create something of a whole picture. Among the tidbits pertinent to The Sleeping Car Porter are the arrest of a white Toronto man in 1920 for being caught with a Black train porter in a hotel bathroom—a fear vividly felt by Mayr’s Baxter (and a more comical source of inspiration: a 2018 CBC article that describes a 45-hour passenger train delay that affected riders near Jasper National Park). These historical tidbits come together to flesh out Baxter’s past, his present anxieties, and, if we extrapolate, his promising future.

If you want to do some more reading by Black Canadian authors, check out our Recommended Reads magazine!