June is National Indigenous History Month, a celebration of the diverse histories, heritages, and present lives of Canada’s First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities. “The Government of Canada recognizes the importance and sacred nature of cultural ceremonies and celebrations that usually occur during this time”, as per the official government website. But just as we at the library were preparing resources to celebrate this month, our country was rocked with a gruesome discovery: the bones of 215 children buried beneath the Kamloops Indian Residential School. A horrifically apt reminder from the universe of our dark history, lest it be forgotten amidst the celebrations.

June is National Indigenous History Month, a celebration of the diverse histories, heritages, and present lives of Canada’s First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities. “The Government of Canada recognizes the importance and sacred nature of cultural ceremonies and celebrations that usually occur during this time”, as per the official government website. But just as we at the library were preparing resources to celebrate this month, our country was rocked with a gruesome discovery: the bones of 215 children buried beneath the Kamloops Indian Residential School. A horrifically apt reminder from the universe of our dark history, lest it be forgotten amidst the celebrations.

I just finished reading Days Without End by Irish writer Sebastian Barry, a Civil War-era novel that is not shy of relating the atrocities committed by colonists in pursuit of an expanding frontier. The 1860s seem a different world but, in the grand scheme of human civilization, it was basically yesterday. We might like to think we’ve progressed beyond the horrors of the past, but the damage done to Indigenous communities lingers today. The last residential school was closed in 1996, to put that into context. And though we’ve finally scrapped the schools, Indigenous children make up 30% of the population of children in foster care. Our country has an actual human rights crisis on its hands regarding Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW). The road to reconciliation is long, and we’re not even close to the end (as of writing this, neither the British Crown nor the Catholic Church has officially recognized their devastating roles in the residential school system).

As part of National Indigenous History Month, the Canadian government is promoting #IndigenousReads, in hopes “to encourage reconciliation by increasing Canadians’ understanding of Indigenous issues, cultures, and history”. Publishers Weekly recently put out an interview with a handful of Canadian and American booksellers and publishers regarding Indigenous literature, highlighting the particular benefit of storytelling in “the reimagining of [Indigenous] lives through the storytelling of contemporary Indigenous authors.” The interview is a hopeful one; with the public interest in social issues growing, publishers are more likely than ever to promote (and seek out) Indigenous voices. And even better news: these titles sell well, proving public interest in the subject and thus encouraging even more Indigenous publications.

Since Indigenous issues tend to be quite low-profile in public consciousness, Indigenous stories are still an emergent market (in terms relative to other minority groups). So it seems that much of the available literature engages with trauma narratives—the suffering and overcoming of it. It’s a criticism that has been (rightfully) leveled at the publishing industry regarding Black and queer stories specifically: it’s always about suffering, or about surviving in the face of tremendous adversity. It’s never just about, like, someone going to get an ice cream cone. Other minority groups have successfully pushed against this narrative rut, demanding stories that feature joy, love, optimism—all things that are perfectly acceptable in cis, straight, white stories, but took years to become mainstream for others. In time, we will likely see more Indigenous stories along those lines as well. For now, healing is still necessary, and there is still much for non-Indigenous folk to learn. To read Indigenous literature is to sit with trauma, but also to discover a recurring theme: perseverance. Like the cultures from which they come, whose languages, rituals and traditions have hung on despite powerful, relentless attempts to stamp them out, Indigenous stories do not succumb to circumstances. Survival, against all odds.

Since Indigenous issues tend to be quite low-profile in public consciousness, Indigenous stories are still an emergent market (in terms relative to other minority groups). So it seems that much of the available literature engages with trauma narratives—the suffering and overcoming of it. It’s a criticism that has been (rightfully) leveled at the publishing industry regarding Black and queer stories specifically: it’s always about suffering, or about surviving in the face of tremendous adversity. It’s never just about, like, someone going to get an ice cream cone. Other minority groups have successfully pushed against this narrative rut, demanding stories that feature joy, love, optimism—all things that are perfectly acceptable in cis, straight, white stories, but took years to become mainstream for others. In time, we will likely see more Indigenous stories along those lines as well. For now, healing is still necessary, and there is still much for non-Indigenous folk to learn. To read Indigenous literature is to sit with trauma, but also to discover a recurring theme: perseverance. Like the cultures from which they come, whose languages, rituals and traditions have hung on despite powerful, relentless attempts to stamp them out, Indigenous stories do not succumb to circumstances. Survival, against all odds.

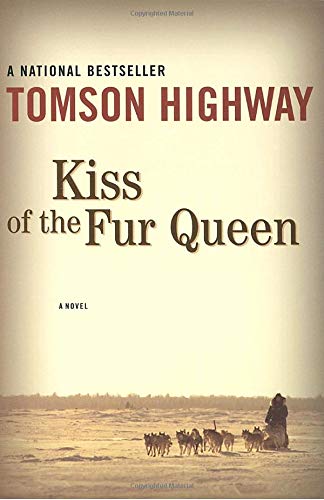

Here at the library, we absolutely believe in the power of the written word for promoting understanding, compassion, and connection across boundaries. Canada has some incredibly talented Indigenous authors, some of whose stories have carved their way into my heart and stayed there since putting the books down. I first read Tomson Highway’s Kiss of the Fur Queen in university, and I don’t think I’ve stopped thinking about it since. The novel is a fictionalized version of author Highway and his brother’s (of the Cree nation) time at a residential school. As you’d expect, it’s not always easy reading; there’s abuse at the hands of the priests who run the school, the scars of which the boys carry with them into their adult lives. Watching over them is the titular Fur Queen, a trickster figure. Highway is usually known as a comedic playwright (see his plays The Rez Sisters and Dry Lips Oughta Move to Kapuskasing) but in Fur Queen he chronicles the divergent paths of two brothers coping with abuse; while Highway’s fictional avatar finds a coping mechanism in music, his brother has a harder time of it (Highway’s brother, a dancer like his fictional counterpart, died of AIDS in 1990).

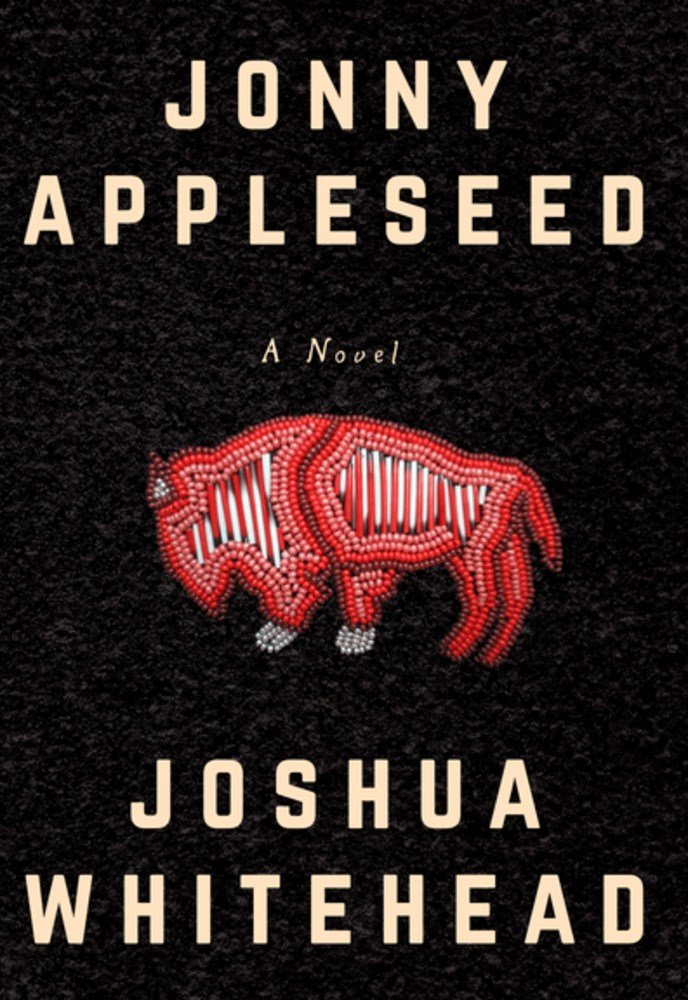

Terese Marie Mailhot’s Heart Berries is a quick, acerbic memoir, which was partly written in a mental institution following a breakdown. The short chapters carry the weight of intergenerational trauma in a Nlaka’pamux community; it’s the weight of Mailhot’s grandmother’s residential school experience, of substance abuse, of her own sexual assault, and of mental illness. Intensely personal, some epistolary chapters rail at Mailhot’s partner with such palpable pain that it comes as a shock to learn that they’re now happily married. Heart Berries reads like an exercise in exorcising demons—and should my description put you off reading it, be assured that Mailhot is in a much better, healthier place now. And one of my newest favourites is the winner of this year’s Canada Reads tournament, Jonny Appleseed by Joshua Whitehead—a fever dream of a novel, like being inside Whitehead’s mind let loose. It is brusque, raw, poetic, explicit, and captivating. From his bleak Winnipeg apartment where he finds employment as a cybersex worker, narrator Jonny takes us on a vivid ride through memories of the reservation, his mother, his grandmother, and the boy he loves. Jonny, like author Whitehead, is Two-Spirit (the “2S” you commonly see in LGBTQ2S+); a concept that doesn’t have a direct correlation in Western culture, but which is loosely defined as “a person who identifies as having both a masculine and a feminine spirit, and is used by some Indigenous people to describe their sexual, gender and/or spiritual identity”. Whitehead is part of the Peguis First Nation.

Terese Marie Mailhot’s Heart Berries is a quick, acerbic memoir, which was partly written in a mental institution following a breakdown. The short chapters carry the weight of intergenerational trauma in a Nlaka’pamux community; it’s the weight of Mailhot’s grandmother’s residential school experience, of substance abuse, of her own sexual assault, and of mental illness. Intensely personal, some epistolary chapters rail at Mailhot’s partner with such palpable pain that it comes as a shock to learn that they’re now happily married. Heart Berries reads like an exercise in exorcising demons—and should my description put you off reading it, be assured that Mailhot is in a much better, healthier place now. And one of my newest favourites is the winner of this year’s Canada Reads tournament, Jonny Appleseed by Joshua Whitehead—a fever dream of a novel, like being inside Whitehead’s mind let loose. It is brusque, raw, poetic, explicit, and captivating. From his bleak Winnipeg apartment where he finds employment as a cybersex worker, narrator Jonny takes us on a vivid ride through memories of the reservation, his mother, his grandmother, and the boy he loves. Jonny, like author Whitehead, is Two-Spirit (the “2S” you commonly see in LGBTQ2S+); a concept that doesn’t have a direct correlation in Western culture, but which is loosely defined as “a person who identifies as having both a masculine and a feminine spirit, and is used by some Indigenous people to describe their sexual, gender and/or spiritual identity”. Whitehead is part of the Peguis First Nation.

What are some of your favourite books by Indigenous authors? Remember to use the #IndigenousReads hashtag if you’re sharing on social media!

If you’re looking for some programming or resources for National Indigenous History Month, please check out the following links:

- Film Talks: our first session will feature a talk by director Kirsten Carthew about her film The Sun at Midnight (available to stream for free on Hoopla!)

- Indigenize Our Minds: a Pow Wow Experience

- A reading list for National Indigenous History Month

- A reading list for the history and impact of residential schools in Canada

- Indigenous Canada course offered by the University of Alberta (available for free through Coursera)