I have a distinct childhood memory of being at some older cousin’s wedding, listening to the Maid of Honour give a speech. She was my cousin’s best friend, and I remember her saying something along the lines of “we can go months without seeing each other, and then pick right back up where we left off.” To little me, the idea of not seeing your friends for months was preposterous. How can you even call yourselves friends, if you’re not seeing each other every day? Of course, as an adult, that speech now makes a lot of sense to me. Even before COVID, it wasn’t unusual to not see good friends for months and months. Keeping in touch is easier now, of course: smartphones and social apps. But in-person hangouts are far less frequent than as kids. Reality isn’t like Friends or New Girl—you probably don’t live across the hall from or in one giant apartment with your adult friends.

I have a distinct childhood memory of being at some older cousin’s wedding, listening to the Maid of Honour give a speech. She was my cousin’s best friend, and I remember her saying something along the lines of “we can go months without seeing each other, and then pick right back up where we left off.” To little me, the idea of not seeing your friends for months was preposterous. How can you even call yourselves friends, if you’re not seeing each other every day? Of course, as an adult, that speech now makes a lot of sense to me. Even before COVID, it wasn’t unusual to not see good friends for months and months. Keeping in touch is easier now, of course: smartphones and social apps. But in-person hangouts are far less frequent than as kids. Reality isn’t like Friends or New Girl—you probably don’t live across the hall from or in one giant apartment with your adult friends.

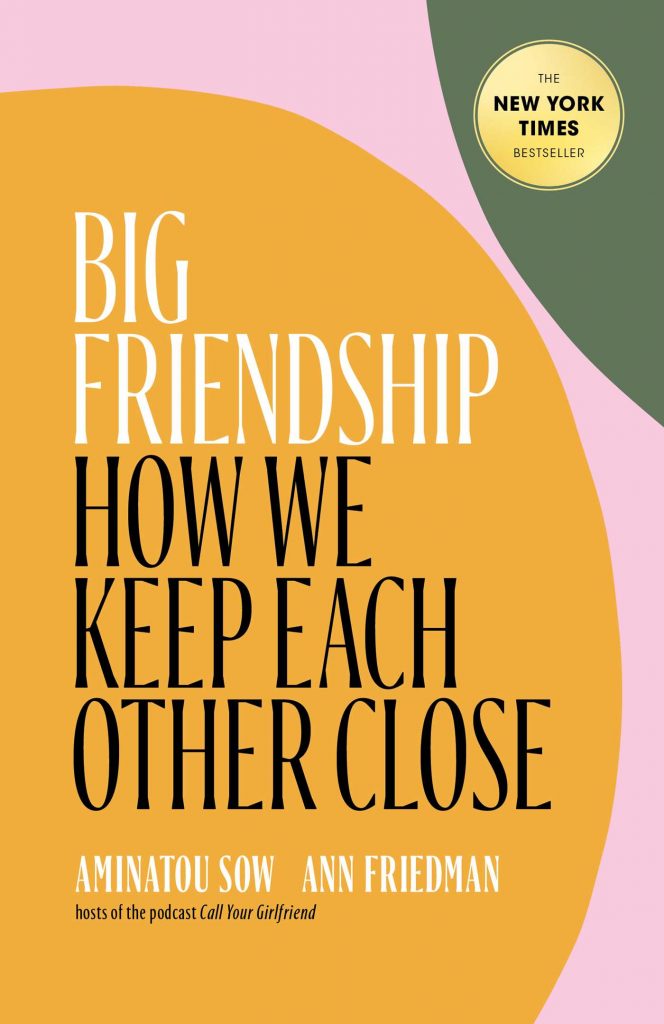

Adult friendships are a lot harder to maintain than sitcoms would suggest, due to competing commitments. Jobs, significant others, children. We’re busy! If you’re an avid podcast listener, you might know Aminatou Sow and Ann Friedman from Call Your Girlfriend, the hit podcast “for long distance besties everywhere.” The show’s manifesto is as follows, from the website: “We believe that friendship—particularly among women and femme-identified people—is a defining, important, and powerful relationship, and that conversations among friends can be the source of incredible social and political power.” A bold statement, and one that’s at the core of their new book Big Friendship, though in a down-to-earth, accessible (and fun!) way.

In Big Friendship, Aminatou and Ann (as they refer to themselves) work through their living example of a successful friendship that has survived all sorts of adult problems. The trick? They simply cared to maintain that friendship. And that meant putting in work, the kind of work we usually associate with romantic relationships (they have, for example, been to Friend Therapy). Big Friendship makes the argument that, though society doesn’t seem to value it as such, deep, lasting friendship is—and always was—a vital part of the human experience.

While much of the book speaks to Aminatou and Ann’s personal experiences, the friends consult other professionals and historians to round out their points. They get into the kind of history that I personally love; the kind that makes you think twice about what you assume to be the status quo. Though friendship might not be the most favoured of relationships today, there was a time where they were considered the be-all-end-all. And we know when that changed! Nobody was more obsessed with the virtue and purity of friendship than the ancient Greeks; Aristotle wrote an in-depth treatise on the subject, and Plato gave us the word platonic. Of course, these philosophies applied to men only—the Greeks were famously misogynistic and did not care a whit for women’s company (insert Greek jokes here).

©Milan Zrnic

But if you thought Greek friendship hewed a little too closely to romance, wait till you get a load of the 19th century! Google “19th century friendships”, and literally all the results are about a phenomenon called the “romantic friendship”. Have you ever read letters between same-sex friends from that time? If you haven’t, you’re missing out. Check out this 1834 letter from one female friend to another: “I do not believe that men can ever feel so pure an enthusiasm for women as we can feel for one another … ours is nearer to the love of angels.” And this one from a man to his (male) best friend, separated after graduating college: “I knew not how closely our feelings were interwoven; had no idea how hard it would be to live apart, when the hope of living together again no longer existed.” Imagine speaking to your friends this way?! (As a side note, this kind of language makes it impossible to divine who, in the past, was actually shacking up with their friends and who was merely being flowery. The debates are endless).

So when did that kind of openly affectionate, lovey-dovey friendship change? In Big Friendship, Aminatou and Ann interview historian Stephanie Coontz, who specializes in the history of marriage. Coontz recounts how in the Victorian era, gender roles became even stricter, forcing men and women into separate spheres (work and home, respectively)—men are from Mars, women are from Venus. Hence the intense, pre-marriage same-sex friendships. Paradoxically, marriage was now viewed as loved-based, rather than economics-based, and the idea of spouse-as-best-friend discouraged married folks from pursuing friendships outside the marriage. Practically, however, the social gulf between men and women didn’t really allow for this (gotta love the Victorians, nothing they did made sense). But the final nail in the Big Friendship coffin was Freud, who strode into the psychology field with his weird sex obsession, and suddenly close same-sex friendships were suspect—“no homo” in its earliest form.

People like Aminatou and Ann—and, as noted in Big Friendship, their friends Isaac and Saeed, for a male example—are doing the work to restore the concept of friendship back to its former holistic, intrinsic-part-of-happiness glory. In an interview with The Atlantic, the ladies pose the question: “What could the world look like if you just let people who do not want to marry each other and who are not blood relatives decide that they want to build a life together?” What “building a life” entails is entirely up to those friends, and would look different for everyone. Aminatou and Ann discovered a gap in language for their Big Friendship, and it seems another fringe vocabulary is developing on the Internet to fill that gap as well. I’ve seen the word “queerplatonic” pop up here and there, to much debate—what exactly is the difference between a “queerplatonic” relationship and, say, lifelong best friends? I’m not really interested in whether there’s validity to the word, but what does interest me is the perceived need for it: there’s a gap in the vocabulary that the Internet is attempting to fill. Really, isn’t this just a return to romantic friendship? Stretching even farther back, isn’t this also just, like, the Greek ideal? It’s not a new concept, just a new, perhaps overly academic, word for it. It is, at the core, repositioning friendship back to its original importance. The point is clear: the status quo is no longer satisfying, and we need to find a new (or, in this case, old) way of valuing our friendships.

It really does come down to caring enough to make an effort to maintain those relationships (at any level, whether it’s a platonic friendship or a romantic one) – we’re so used to seeing life hacks (e.g. “how to lead a happier life with just 7 simple changes!”, etc.) that being told it’s actually about putting in the work – and maybe not caring that your friendship doesn’t conform to what people think of as friendship nowadays – is actually refreshing. Shocker: you have to put in work for your friendships. I would argue that close friendships don’t even need to just be between same-gender pairs, once we stop making it weird by speculating endlessly about whether they’re /actually/ together or “just friends”. (About which: why are friends reduced to “just”? Are romantic relationships inherently more worthy pursuits than platonic friendships? Also the heteronormative assumptions! It sounds to me we should be reconsidering our priorities here.) But now that we’ve got more vocab available to us, the categories just get muddier and muddier: is this intense friendship of yore (the ones who weren’t actually shacking up together) a romantic if asexual relationship? Or platonic? Except I think perhaps the real question is: does it really matter if everyone involved is content with the way things are??

As an aside, I kind of wish we still wrote like this to our friends – these are absolutely incredible and I love the openness in these letters! (If perhaps a bit exaggerated in its intensity? Perhaps; perhaps not.)

The thing you said about being “just friends” is exactly it! Why do we say “just”? It’s definitely because friendship is on a lower rung of the relationship ladder, which is why it’s so easy to let them go. You work on a romantic relationship, but if a friendship falls apart, well, that’s just life! That’s part of what the book tackles. They do focus primarily on friendships between women, since it’s a very personal book about their friendship, but you’re right, different-gender pairs might need even more work!

I do agree with you about adding more vocab to something that perhaps doesn’t need to be described in so many words….like, at the end of the day, it’s all friendship. Let’s just adjust what we understand that to be! Anyway. To each their own.

And the letters are so entertaining! I definitely understand it to be a trend, so I do think the language was a bit exaggerated to fit the mode at the time, but they’re just so open and loving!