Do you love discussing movies? Then join us monthly at our Film Talks program! We’ll watch films, chat with viewers, and host some special guests!

2021 marks the 20th anniversary of Moulin Rouge and the 25th anniversary of Romeo + Juliet, two absolute bangers brought to us by the visionary that is Baz Luhrmann. You’d be hard-pressed to find a more polarizing director. You can love him, or you can hate him, but you’ll never sway the other team to your side. Luhrmann’s style can generally be described as maximalist—but that wouldn’t truly do it credit. It’s maximalism at the top end of the gauge. It’s maximalism on every party drug known to man. It’s fireworks and swirling colour and dizzying camera cuts, for no other purpose than to throw you off your balance and to pitch you head-long into a world of high camp, high energy, high drama—just high, to be perfectly honest. Luhrmann looks at maximalism and says, “sure, more is more. But most is best.”

As a viewer, you either eat up the spectacle or you throw it away; you’ll notice that both positive and negative reviews use the same language to describe his work, and it’s up to you how to feel about it. Are you seduced by the “tour de force of artifice, [the] dazzling pastiche of musical and visual elements” (a positive review) or put off by the “Gorgeously decadent, massively contrived, and gloriously superficial” ones (a negative review)? One thing is for sure: you will have a strong emotional reaction either way. You don’t just watch a Baz Luhrmann film. You need to strap in and prepare for whiplash, because he is about to assault all five of your senses and maybe a sixth.

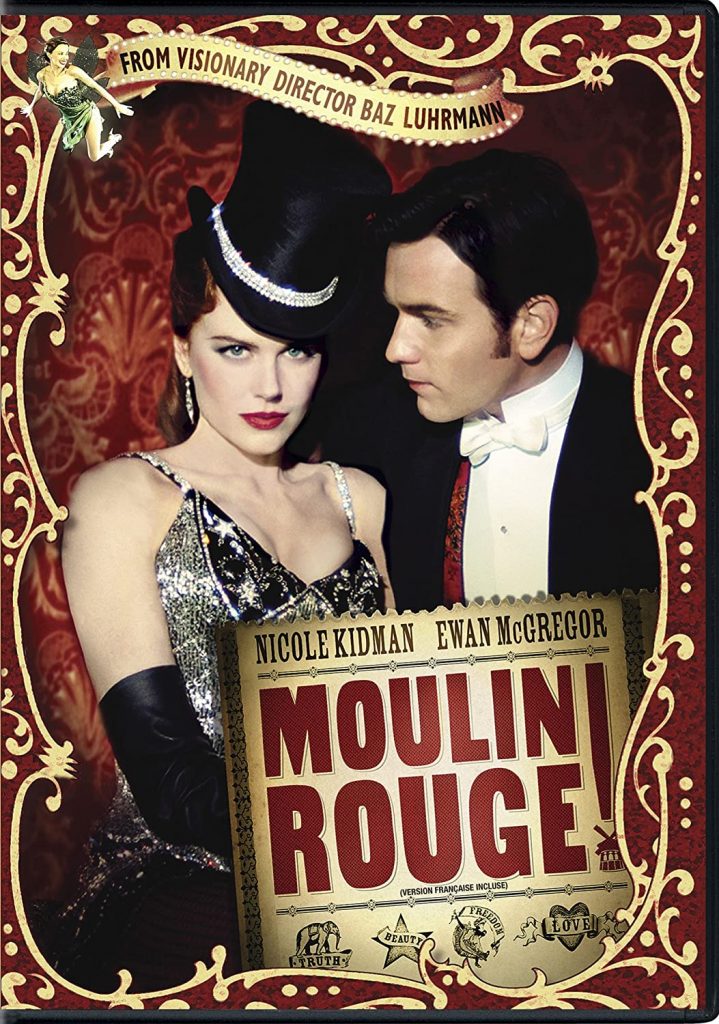

But to reduce Luhrmann’s work to artifice and superficiality would be to miss the point. Yes, his films are a love letter to excess, and bring new heights to the term “chewing the scenery”. Yes, aesthetics are front and centre. But Luhrmann uses all these tools—and, truly, every tool in his belt—to get to the truth of the matter: he can laser-focus on an emotion or a theme, and then yank on it until it’s at the surface in its most raw form. The heightened artifice brings it out. Take Moulin Rouge, for example. The film high-kicked its way into theatres in June 2001, following a decade marked by too-cool-for-you-irony (and just before the gravity of 9/11). It’s a fin de siècle burlesque jukebox musical about a penniless writer (played by Ewan McGregor) and a high-end courtesan (Nicole Kidman) who fall in love at the titular cancan venue. It’s a film whose theatrical climax features a man growling a tango version of “Roxanne” by The Police. The two main characters fall in love over the course of one mishmashed pop song—maybe two, if we’re being generous. Kylie Minogue has a cameo as “The Green Fairy”, a hallucination brought on by absinthe. The villain is simply named The Duke (but you have to say it dramatically: The Djuuke) and he performs an extended, silly version of Madonna’s “Like a Virgin”.

None of this should work; it should be cringey in its earnestness, its bizarreness, its stagey commitment to archetypes and tropes. But it’s not. Luhrmann drew inspiration from Bollywood films, following a preset pattern: “A couple meets, they’re torn apart by outside forces, one half pretends to betray the other, they sing a song that brings them together, and either they ride off into the sunset or someone dies”. But more than just plot structure, the Bollywood inspiration prevents the film from becoming too afraid of its own ridiculousness: the ridiculousness is the point. The film lives up to its creed of “Truth! Beauty! Freedom! Love!” because it fully believes in it. You simply have to take it for what it is, in all its flamboyant glory.

Because of his propensity for intense emotion over realism, I wonder if the age at which you’re exposed to Luhrmann’s work might have some effect on the way you receive it. Moulin Rouge came out in my preteen years, and it was a revelation to me. It basically imprinted on me; I have since visited the actual Moulin Rouge in Paris more than once (well, the outside of it—those shows are stupidly expensive) and hung out in the Montmartre neighbourhood, feeling a sense of kinship (I even have a tattoo related to the area). The songs shaped my music journey as I entered adolescence. My dad, who was forced to sit through many a screening, was the one pointing out to me, “this song is by David Bowie. This song is by Nirvana”, and then I would go onto LimeWire and painstakingly download each song (which, if you remember LimeWire, could take weeks). And let’s not talk about the fact that somewhere there is footage of my friends and I performing the (wildly inappropriate for our age) “Lady Marmalade” dance in someone’s basement. For some of us, the film was a cultural moment that, like Titanic a few years before, we embraced as part of our cultural vocabulary. Moulin Rouge would go on to inspire more movie musicals (a genre that was all but dead at the time), including the satisfying Chicago and the less-than-satisfying The Phantom of the Opera, and a 2018 Broadway show of the same name.

Speaking of Titanic, the Leonardo DiCaprio-starring vehicle Romeo + Juliet also celebrates a milestone anniversary this year. Released in 1996, I admittedly was too young for it at the time—but, like Moulin Rouge, was lucky enough to discover it in my preteen years. And a similar thing seems to have happened upon its release. At the time, it wasn’t exactly well-received. The film seemed to baffle adults, who couldn’t quite reconcile the Shakespearean dialogue with American accents, or what Vulture calls the “bombastic, glittery, MTV-generation melodrama” of it all. We all know the 1968 Franco Zeffirelli version, right? The one starring Olivia Hussey and Zac Efron’s doppelganger, Leonard Whiting? If you had to study the play in English class, chances are you saw one of these two films. Many would argue that, because the 60s version is set in the correct era, and has British actors, it’s the better adaptation. But I would argue that as the spirit of the thing goes, Luhrmann knocks it out of the park.

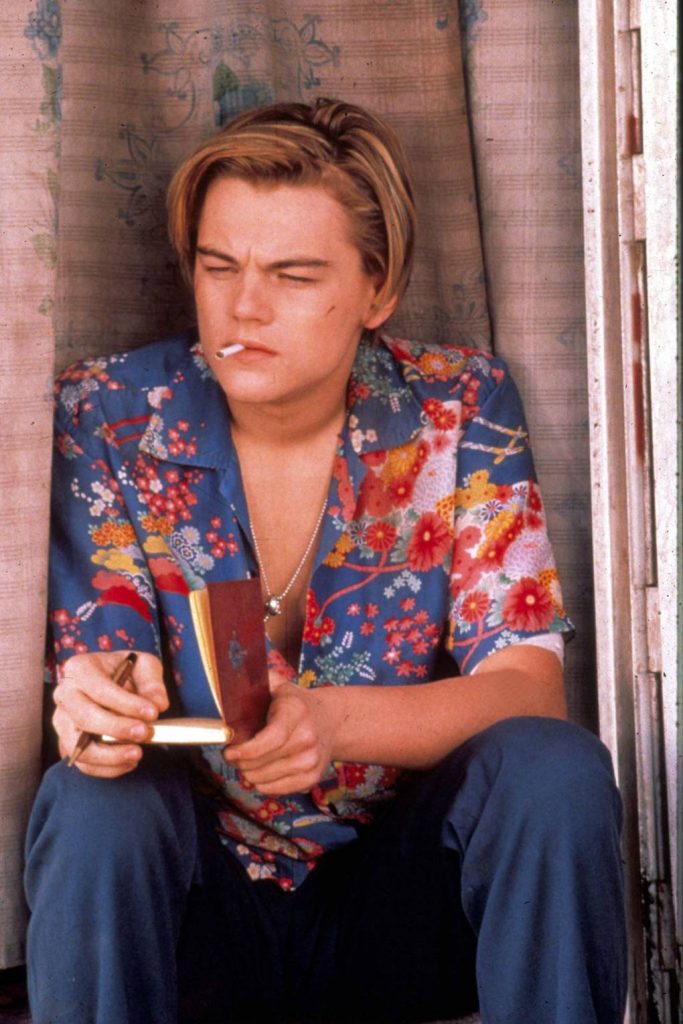

Shakespeare’s play is set in sun-drenched, sweltering Italy—the weather is important, because it reflects the mood of the characters (hello, pathetic fallacy!). The Montague boys are hotheaded, irrational, constantly looking for a brawl. Luhrmann moves his version to “Verona Beach”, a Venice Beach-esque town that just looks like it’s 40 degrees Celsius (it was filmed mostly in Mexico City). As the boys prowl around town in their Hawaiian shirts and their loud, fast cars, getting into gun fights at the gas station, Luhrmann nails the youthful idiocy of Shakespeare’s original characters. Remember, this is a play about two young dummies who become so obsessed with each other that they both end up dead (to throw it back to Sassy Gay Friend: “I think you’re fourteen and you’re an idiot. You took a roofie from a priest. Look at your life, look at your choices”).

And then there’s the absolutely iconic interpretation of Mercutio that I doubt will ever be topped, whose grand entrance sees him pulling up in a red convertible to the disco hook of “Young Hearts Run Free”, dressed in a sparkly silver skirt and heels, putting on lipstick and laughing maniacally—then going on to recite the Queen Mab speech like his life depends on it. The original Mercutio was already a scene-stealer, with his quick wit and dirty jokes, but Luhrmann’s version looked at the OG, put on a wig and said, “hold my beer”. It’s an admirably bold interpretation, leaning into the ambiguity of Mercutio’s feelings for Romeo (a taunting Tybalt spits, “Mercutio, thou art consort’st with Romeo?”). Harold Perrineau, the actor behind the legend, explains that Luhrmann wanted the boys to be a little bit in love with each other—but in that intense, infatuated teen way that doesn’t necessarily imply anything sexual. There is a hurricane of emotion roiling among all these characters at all times. Do I think Shakespeare would look at a rain-drenched Romeo, scream-crying in the street while waving a gun around, and be proud? I sure do (and, as he’s proven time and again, nobody can scream-cry quite like Leo).

And you know who got all this? The youth, that so called “MTV generation”. Imagine being in the midst of puberty and seeing Romeo’s intro for the first time: those floppy blond locks, that glorious scowl at the camera. Or how about Juliet leaning over the famous balcony, dressed as an angel while fireworks burst overhead? The reaction is visceral. It’s obviously very hard to get kids into Shakespeare; the plays are intended to be watched, not read, and the language is hard to wrap our modern heads around. But when all else fails, people understand emotion—and that’s what Luhrmann gives us. And as those young viewers of the film, enthralled by its high-octane vibrancy, grew up, they carried their love of the film with them, and it is now a certifiable cult classic (for a clear-cut example of this, critic Roger Ebert gave the film two stars in 1996, saying “This production was a very bad idea”. In 2020, a Roger Ebert staff writer posted an article calling the film “as irreplaceable as ever”. How the turntables!).

What remains to be seen is if Luhrmann can pull off another Moulin Rouge or Romeo + Juliet, or if they were two perfect, lightning in a bottle masterpieces. His 2013 adaptation of The Great Gatsby will be the next test of time (ignoring Australia, which is stylistically different from his usual fare). From where I stand, it doesn’t hold a candle to the others; it feels almost like Luhrmann-lite, holding back its full potential for that trademark chaos and ending up in some lukewarm middle ground. Not quite a straight-forward adaptation, not quite wild enough to compete with its predecessors (even the Gatsby party scenes are more restrained than the Capulet ball in R+J or the “Cancan” scene in Moulin Rouge). It’s too sleek and CGI-heavy, lacking that almost tangible Luhrmann gaudiness. More broadly speaking, it didn’t kick off any notable trends either (R+J was followed by other modern teen Shakespeare adaptations like Ten Things I Hate About You and She’s the Man), aside from renewing public misinterpretation of the Fitzgerald story (it is actually not about how fun the 1920s were). The Great Gatsby is just not as memorable, precisely because it is too hesitant. It doesn’t believe in itself as much the other two do. Or do I only think that because it came out when I was a jaded adult, and not an impressionable youth? Only time will tell! In the meantime, if anyone needs me, I’ll be singing both parts of “Elephant Love Medley” in my car.

It’s funny that you mention The Great Gatsby wasn’t chaotic and extravagant enough, since the lush visuals of the parties was basically the only thing I enjoyed about the adaptation when I saw it in theatres. I don’t really remember much about it apart from that impression though, so maybe letting the chaos run free would actually have made the entire film better! We did watch this Leo version of Romeo and Juliet in class, and the scene with Juliet as an angel leaning out the balcony is basically all I remember about it today. I can’t say the entire film was my jam (R+J were, as you say, dummies, and as a teen I had no patience for it), but you’re making me want to revisit the movie and possibly revise my first impression of it. Thank you for introducing me to the Sassy Gay Friend intervention, which basically sums up the entire play, and the collection of Leo scream-crying, which I didn’t realize I ever wanted.

LIMEWIRE. What a time.