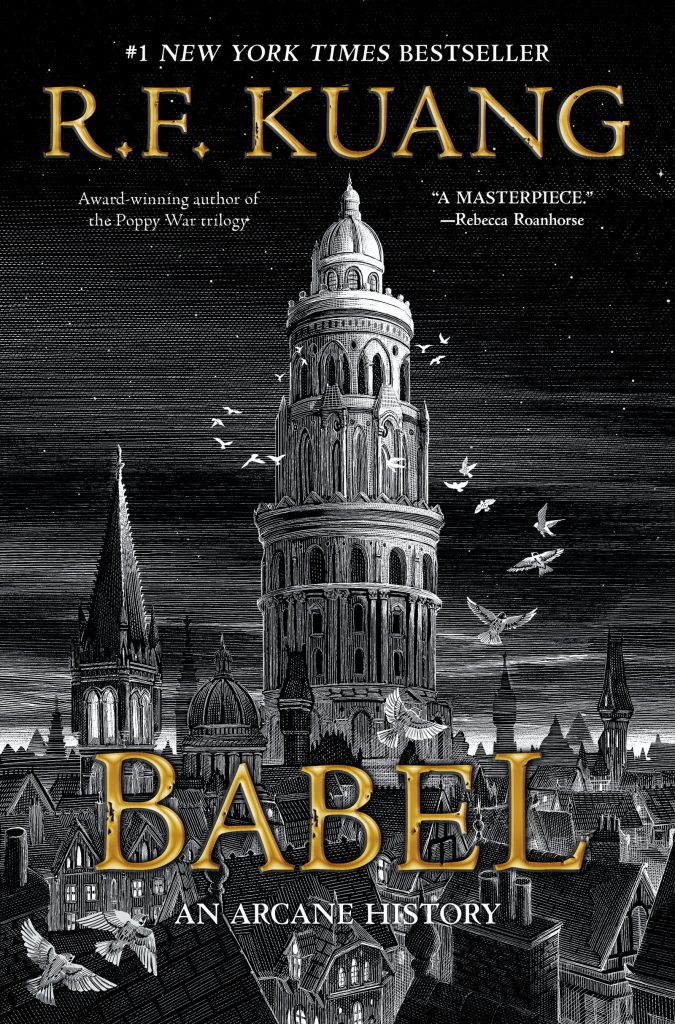

Babel (full subtitle: Or, the Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of the Oxford Translator’s Revolution) by R.F. Kuang is a big, bold, incredible conundrum of a novel. Anything clocking in at over 500 pages is already going to be asking a lot from its readers. And that title? Music to my history nerd ears (eyes?), but what a mouthful! From the jump, Kuang is telegraphing what you’re about to sink into, and that is a dense, at times challenging, historical epic. Babel follows Robin Swift as he’s taken from his home in Canton to be raised in England, priming him for a lucrative career in Oxford’s translation department. But things aren’t all what they seem, and Robin quickly gets caught up in an underground, anticolonial movement called the Hermes Society.

This book is marketed as a fantasy, but it’s light on the magic. In this version of Industrial Revolution era Britain, the gilded Oxford University has a Royal Institute of Translation (I googled: not a real thing) based out of a tower aptly named Babel. This institute works by translating and inscribing words into enchanted silver bars, which function like a source of energy for their owners. So, countries that can afford more silver bars gain more power. Kuang doesn’t imagine much of an alternate history here; Britain is the dominant force in the silver trade and thus has the strongest colonial power—just like real life. Truthfully, not much is different than actual British trade history. I know some readers were frustrated by that, but it doesn’t bother me. Just approach the novel like historical fiction with some slight fantasy elements, and that should mitigate any disappointment.

Rather than the more typical elements of fantasy fiction, the magic in this world is the act of translation itself. This might be where reader reactions diverge. Kuang, a scholar through and through (she currently has two Masters, one each from Oxford and Cambridge, and a PhD in East Asian Languages and Literature from Yale) is not shy about loading the text with thorough explorations of linguistics and the history of language. Your mileage may vary on how interesting this is; as someone who minored in linguistics, I am always happy to see the word “Proto-Indo-European” appear in the wild. Give me all the etymologies!

Kuang’s insights on translation give the reader a lot to chew on, such as when she states that “an act of translation is necessarily always an act of betrayal.” Translating from one language to another is never a game of one-to-one; something is always lost or misconstrued in the process (in fact, the power of silver bars is captured in this shadow region of mistranslation—the more the translator can comprehend both the original meaning and the new one, the stronger the power). Some concepts exist in one language’s lexicon but not in others: the German schadenfreude (feeling joy at someone else’s pain), the Norwegian forelsket (the feeling of falling in love), the Japanese wabi-sabi (finding beauty in imperfection), the Welsh hiraeth (longing for a home that no longer exists)…none of these words have an obvious English counterpart (and can’t always be accurately captured, even in a long-winded way). English tends to just adopt these unique words (think of the explosion of hygge in the past few years); whether you see that as a feature or a bug is debatable.

The most compelling aspect of the novel for me, besides the linguistics, is the tension in Robin’s academic career as a Chinese-born student at the elitist Oxford. Kuang writes from her personal experience here, as a scholar born in China, raised in the United States, and pursuing higher education at the top schools in England. During her studies, she found herself misconstrued due to the differences in American and British slang, but was most affected by the assumption that she was visiting Oxbridge as a tourist, rather than as a student. She gives Robin these experiences—heightened by the (more) open and rampant racism of the 1800s—and complicates it with the duality of oppression and privilege. Robin, by virtue of his race and country of origin, is oppressed by the powerful English, but at the same time, as an Oxford student, is given access to that very source of oppression—and benefits from it. Kuang confronts these two truths, how you can both long for and revile the same thing, and hold those conflicting emotions within you at the same time.

I do wish this level of nuance was carried through the course of the novel, though. Babel suffers from a hyper-awareness of itself as a book, and Kuang’s own voice (rather than Robin’s) is never far from the narrative. There’s a fear of just letting the story be. There’s a defensiveness to the writing, as though anticipating an argument, that can only be born of someone who has been through the Twitter trenches (as a young author, I’m sure Kuang has been there). Kuang includes a manifesto before the story even begins, defending her choice to represent Oxford a certain way. And that kind of makes me sad! We’ve seen a rise in hostility to art these past few years. There’s also an uncomfortable trend of taking everything at face value, with some readers believing that, by including something in a book, the author automatically agrees with it. It’s very, very damaging. Imagine Donna Tartt having to defend The Secret History? “Just so we’re clear, murder is bad and these characters are bad people. You’re not supposed to agree with them.” It’s easy to call it a Disneyfication of morality, though even Disney itself used to have more bite (can you imagine how people would react to the song “Hellfire” today?!). Kuang’s narrative tone seems to be a response to this. This sort of hyper-awareness is not unique to her, of course; the TV show She-Hulk constantly reminded viewers that it was meta-aware. Playing tennis against an internet mob while creating art seems like an exhausting experience!

Anyway, as you can tell, Babel is a fascinating, thought-provoking read that spurs discussion beyond the limits of its pages. So even with my criticisms, I’m still happy to have it sitting on my bookshelf (plus, that cover? Gorgeous)!